Any position which a man has occupied in the new industry...

Has been, and is now, occupied by a woman

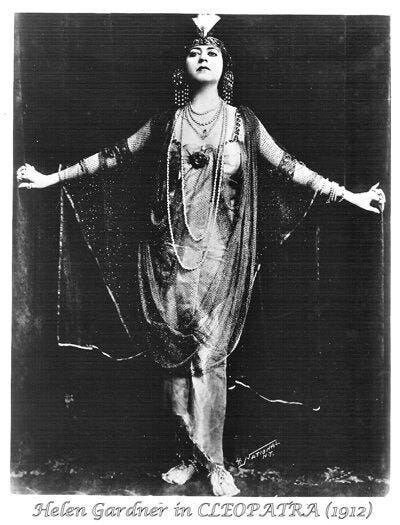

After a few decades of shorts that were minutes or even seconds long, the first (or certainly one of the first, it’s hard to pin down exactly) feature-length film (at 6000 feet) made in the US was Cleopatra, in 1912.

It was the debut production of The Helen Gardner Picture Players. Helen Gardner was a successful stage actress who was wooed by Vitagraph in 1910. With the creation of The Helen Gardner Picture Players, she became the first actor ever (female or male) to form their own production company. and she continued writing, directing and producing well into the twenties.

Cleopatra pre-dated Birth of a Nation by two years.

Though Helen later directed, she hired her lover, Charles Gaskill (she was happily separated but not divorced from her husband, and remained so until his death in 1964) to direct Cleopatra. The first feature to be directed by a woman in the US was an adaption of The Merchant of Venice in 1914. It was directed by Lois Weber.

So any time you hear anyone bemoan the fact that the “first feature film” was an ode to racism directed by a well-known misogynist, feel free to point them right here…

Lois Weber was born in Pennsylvania on June 13, 1879 into an artsy family. Her dad worked at the Pittsburgh Opera Theatre, and Lois was considered a child prodigy on the piano. She said of her childhood. “I don’t remember a time when I did not write - certainly I’ve written and published stories since I could spell at all.”

It is worth bearing in mind that a decent majority (though not all) of these early female film pioneers came from privileged backgrounds. Helen Gardner’s company was financed by her mother. Lois Weber and screenwriter Frances Marion were from solidly middle class families and Julia Crawford Ivers was properly rich. Anita Loos seems to have needed to support herself from a young age, but her brother became a doctor so education was at least accessible to their family.

Lois Weber entered theatre as an actress, touring with various stock companies from 1904. There she met and married actor and director Phillips Smalley. Not long after their marriage Weber started writing and selling film scenarios from home on a freelance basis. In 1908, Weber and Smalley were hired as a writing-directing-producing team by the American Gaumont Chronophone company.

The roles of writer, director and producer, were fluid and even the terms interchangeable in those days.

Weber and Smalley did work more or less as a team until they divorced in the early twenties, but it’s important to note that everyone, including Smalley, saw her as the senior partner and creative brains of the outfit. He used to refer to their joint projects as “Mrs Smalley’s pictures,” so I think it’s fair to say he knew his place.

American Gaumont was owned and operated by another husband and wife team, Alice Guy Blanché and Herbert Blanché. If you’ll recall from last week, when Alice Guy asked her boss Leon Gaumont for permission to explore making dramatic films in the 1890s, he dismissed her idea as girlish nonsense. Not even a decade later, he financed her own movie studio in New York. I’d like to think he knew his place too...

After a couple of years, Weber and Smalley moved on to the Rex Motion Picture Company, very quickly becoming what we might call today the creative directors. Rex then amalgamated, with five other small companies including the Independent Picture Company (or IMP, of “Florence Lawrence definitely isn’t dead!” fame), to form a studio you might have heard of, Universal.

In 1913 they all headed for the California sunshine and settled “Universal City” (which is still its own privately owned territory outwith Los Angeles).

Universal City quickly became what the Google campus was to us a decade or so ago, more than a workplace, a lifestyle, a symbol of a brand new and pioneering industry. It had its own police force and mayor (more on that in a moment) and offered tours to movie fans from day one. The slogan advertising its opening day was:

See how slapstick comedies are made. See your favorite screen stars do their work. See how we make the people laugh or cry or sit on the edge of their chairs the world over!

The tours were put on hold in the late twenties, when talkies meant that they couldn’t have members of the public oohing and aahing over their favourite actors while they were working. Of course, as we know, they resumed tours in 1964 by creating a theme park separate from the working studio. Long before that, though, Laemle added a zoo to encourage tourists.

A zoo. Lions and tigers, in the same space where people were making movies. In addition to the fact that fans were strolling around watching their “favorite screen stars do their work.” Just imagining the chaos makes my day.

In the teens, Universal was famous for its lady directors - in fact there were more female directors working at Universal than at all the other studios combined. In addition to Lois Weber, the “Universal women” of the teens included Ruth Ann Baldwin, Grace Cunard, Eugenie Magnus Ingleton, Cleo Madison, Ida May Park, Ruth Stonehouse, Lule Warrenton, and Elsie Jane Wilson.

And as it happens - within the very low bar of today - Universal doesn’t do too badly, hiring 7.1% female directors, compared to Paramount’s 4.7% or Warner Brothers’ 2.3.

It’s often argued that this was for reasons of economy.

While the top female directors and writers often out-earned their male peers, then, as now, women tended to work for less, and Universal was all about that bottom line. Out of all the studios in those very early days, Universal was probably the most business and profit minded. So on one hand, they may have been hiring women because they were cheaper, but on the other: they clearly trusted women to churn out profitable films.

In 1913, Universal City elected Lois Weber as mayor, who in turn appointed actress Stella Adams as chief of police. In Women of Early Hollywood, Karen Ward Mahar asks “was this feminism, or was it spectacle?” and, to be honest, the jury’s out. In the same way that we can all be cynical about brands jumping on the woke trend of the moment, it may be that Carl Laemle — let’s face it, the inventor of both celebrity gossip and the movie star — may have been more PR visionary than true feminist. However, even if that was the case, the notion that feminism as a concept was sellable in 1913, is pretty arresting.

One of Lois Weber’s first productions for Universal was 1913’s Suspense, which is basically the blueprint for every thriller made since. It establishes several thriller techniques that Hitchcock gets all the credit for. In 1913 Hitchcock was a wee boy at school.

We often imagine the very early silents as a bit amateur and clunky (and many were), but the cinematography in Suspense wouldn’t be out of place in a movie released today. There’s a sequence of really fast jump cuts between the husband in the car, to the wife hiding with the baby, to the baddie breaking into the house, that’s classic thriller movie tension building. Put it this way: half the thriller tropes that Scream parodied can to be found in Suspense.

It’s worth a watch. Don’t forget the lions and screaming fans: